One hundred years of education, culture, community, and controversy from 1904 to 2004

by Roland Legiardi-Laura

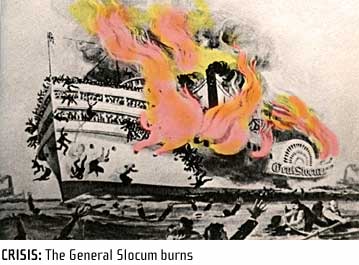

Ground was broken on June 12th, 1904 for the city’s newest public school construction project just three days before the worst civilian disaster in American history (prior to 9/11). More than 1000 people, mostly women and children died when the General Slocum, a ferry boat on holiday duty, burned and ran aground on North Brother Island in the East River. It was the annual church outing for the largely German-American community of the East Village and the loss of so many of the neighborhood’s youngsters devastated the community. Despairing remnants of families moved away by the hundreds and by the time P.S. 64 opened its doors in the fall of 1906, the churning Lower East Side had ceded this plot of land to the latest wave of immigration, Jews from Eastern Europe.

C.B.J. Snyder, New York City’s brilliant and prolific master designer of public schools was in his prime. With each new building, Snyder refined his vision and added important innovations. P.S. 64 would be no exception. Rendered in the popular Beaux Arts style of the day, the school was laid out according to Snyder’s recently developed H-plan. This allowed the maximum of light and fresh air for each classroom. The H-plan also created a grand courtyard entrance for each school and permitted Snyder to place the schools in mid-block locations away from the noisy, crowded and polluted avenues. Large double-hung windows in triptych format were also incorporated into the design. Ventilation and sunlight were then considered the keys to health for America’s cramped, teeming, immigrant quarters.

With P.S. 64, Snyder introduced yet another jewel in his crown of educational innovation: The ground floor Auditorium. The problem he addressed with this simple and elegant stroke of design was Assimilation. How to help these new arrivals to America become effective, contributing members of their communities. How to bring them into the dominant culture. How to accustom them to the ways of our democracy? The ground floor auditorium was an inspired solution. By providing free public assembly space, not just the children but the parents as well, could enjoy the fruits of our society and learn it meaning.

The first time we read about P.S. 64 is in December of 1907. The barely year-old school had become one of the hosts for a myriad of free lectures offered around the city. The New York Times in its weekly listing of evening talks offers up, Camping in the Rockies, by Miss Mary D. Fisk. One can easily imagine the straining faces of the tenement neighbors as they envisioned themselves trekking over the snow-capped peaks of the Great Divide. The lectures and talks become a staple of school life and cultural imprinting at a time when radio and television were only dreams. On a given night on East 9th street you might find yourself sharing a packed auditorium listening to speakers like A. V. Williams Jackson recite Persian Mystic Poetry, or Dr. Edwin E. Slossen expound on The Panama Canal.

During the summer of 1911 P.S. 64 became the first Public School in the City to offer free open-air professional theater to the public. One of the reasons the school was chosen to premiere the series is because it was the first school in the city to have electric lights in its yard. Julius Hopp, director of the Theatre Centre For Schools tried unsuccessfully to stage The Merchant of Venice on the raised courtyard facing 10th street. The noise from the trolleys rumbling down 10th street made the performance inaudible but the thousands of people gathered across the street, packed onto the courtyard and peering from the tenement windows were treated to an impromptu rendition of Kipling’s Gunga Din, recited by Sydney Greenstreet, one of the actors in the production. (Greenstreet became famous as the “fat man” in The Maltese Falcon and Casablanca.) Undaunted, Hopp regrouped and presented the play two days later in the school auditorium. The thrilled audience got a chance to see the young Greenstreet and Warner Oland (later to play Charlie Chan) in Shakespeare’s grand Comedy. Needless to say, the harsh stereotypical imagery of the play was not lost on the neighborhood’s burgeoning Jewish community.

In the 1920’s P.S. 64 was a required stop for politicians campaigning in New York City. Governor Alfred E. Smith, Mayor Jimmy Walker, and Franklin Delano Roosevelt all recognized how important it was to make time to speak in the school’s auditorium. Walker railed against his opponent, then Mayor Hylan, Governor Smith confronted the Hearst News Empire, and Roosevelt assessed his strength with Jewish voters by the neighborhood turnout for his speech at P.S. 64.

Beginning with the School’s second principal, William E. Grady, P. S. 64 became known as a place of educational innovation and experimentation. Grady, who rose to the post of Associate Superintendent of the City School System, used P. S. 64 to develop and test what became known as the Ettinger Plan. In the years just prior to WWI there was a fierce battle to make schooling mimic a model of corporate efficiency and productivity. Plans like the Ettinger program and the Gary Plan of William Wirt were strongly opposed by the newly minted Americans who felt their children were being shunted into poorly rewarded vocational and manual careersÐprecisely the reason they had fled the rigid European class structure. The most vociferous opponents to this planned tracking were the Jewish immigrants who rioted in the streets of New York for several weeks in 1917.

From the school efficiency battles of the pre-war years grew the psychological and intelligence testing movement of the early 20’s. Once again, P.S. 64 was at the forefront of this movement. A young educational innovator, Elizabeth Irwin, (The founder of the famous Little Red Schoolhouse in Manhattan), worked at P.S. 64 from 1912 until 1921. While there, she devised a classification system for students predicated on the scores of their IQ tests. The controversial program won acceptance based on its success at P. S. 64 and in 1922 the first large scale IQ tests were performed on more than 40,000 City schoolchildren.

P.S.64 burst into the newspapers again in 1950. This time two teachers from 64 out of a group of 8 citywide were accused by the Board of Education of being Communists. The McCarthy mindset had found fertile ground within the framework of institutional compulsory schooling. The Superintendent of Schools, Dr. William Jensen, began the spectacle by suspending the teachers without pay. The hearings complete with secret witnesses, noisy protests, a gaggle of lawyers, and culminating administrative trials stretched into early 1951 when all eight were judged culpable and dismissed from their positions. David Friedman had taught for 20 years at P.S. 64 and Abraham Lederman, the President of the New York Teacher’s Union, had been a math teacher at 64 for 23 years. Lederman remained President of the Teacher’s Union until his death in 1963 at the age of 55.

Throughout its significant history as a school P.S. 64 was consistently turning out wonderful young students. Perhaps no public grade school played a greater role in guiding and shaping the creative dreams of immigrant children. Yip Harburg, the man who wrote the Lyrics to The Wizard of Oz and such classic songs as, Brother Can You Spare a Dime and April in Paris says of his days at 64: “My passion to be an actor was consuming. Luckily, the public school I attended, P. S. 64 had a lovely stage. When the teachers found that I was a talented actor, they had me on all the time.I won prize after prize for acting and reciting. Miss Wiseman at P. S. 64 took me and two other kids in the class to see Maude Adams in Peter Pan. I think that experience had something to do with my love for fantasy.”

Sam Levene, the great comic actor, who appeared in scores of Broadway Plays, in such roles as Nathan Detroit in Guys and Dolls, Patsy in Three Men on a Horse, Finkelstein in Dinner at Eight and over 100 films such as The Champ, Justice For All, The Babe Ruth Story and, Sweet Smell of Success, was a graduate of P.S. 64. Morris Green, who produced Cole Porter’s Greenwich Village Follies, Louder Please, and the Broadway version of Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under The Elms, attended 64. AndJoseph Mankiewicz, Oscar winning screenwriter, producer, and director who made such films as All About Eve, Woman of the Year, The Philadelphia Story, Julius Caesar, The Quiet American, Guys and Dolls and Cleopatra spent his grade school years learning at P.S. 64.

Finally in the late 1970’s when the population of the neighborhood could no longer support the school it closed. But shortly after its doors shut they were reopened and the cultural work of the building continued. For the next 20 years the old school building was known as Charas/El Bohio a vibrant community arts and education center. The demographic of the neighborhood had changed, now the new Latino and African American-American residents took advantage of the space. Spike Leescreened his first student film in the Auditorium, Luis Guzman and John Leguizamo performed on the stage. Choreographers rehearsed in the classrooms, painters created studios out of the empty spaces, children studied poetry and martial arts, and everyone still felt as they had almost 100 years earlier, that this building, this space, welcomed and nurtured them.

Even now as the building has become an object of sharp contention and controversy since it passed from the hands of the community to a developer in 2001, it still accurately reflects the struggles of the neighborhood people to determine and to enrich the direction of their lives.

”Over the Rainbow” Composer Yip Harburg and P.S. 64

(From the book Who Put the Rainbow in ‘The Wizard of Oz’? By Edgar Yipsel Harburg)

“My passion to be an actor was also consuming. Luckily, the public school I attended, P.S. 64, had a lovely stage. When the teachers found that I was a talented reciter and actor, they had me on all the time… I won prize after prize for acting and reciting.

“The next great impact that I remember, which had some connection with my work, was a very sweet lady, a Miss Wiseman, with blonde hair, at Public School 64 on Ninth Street and Avenue C, who took me, took three kids in the class, because we were the top of the class, to see Maude Adams in “Peter Pan.” I’ve kept this picture of Maude Adams as Peter Pan all this time. And I think that experience had something to do with… my love for fantasy.