Tompkins Square Park has witnessed many wild episodes over the years, but nothing makes people smile quite like memories of Wigstock.

by Robin McMillan

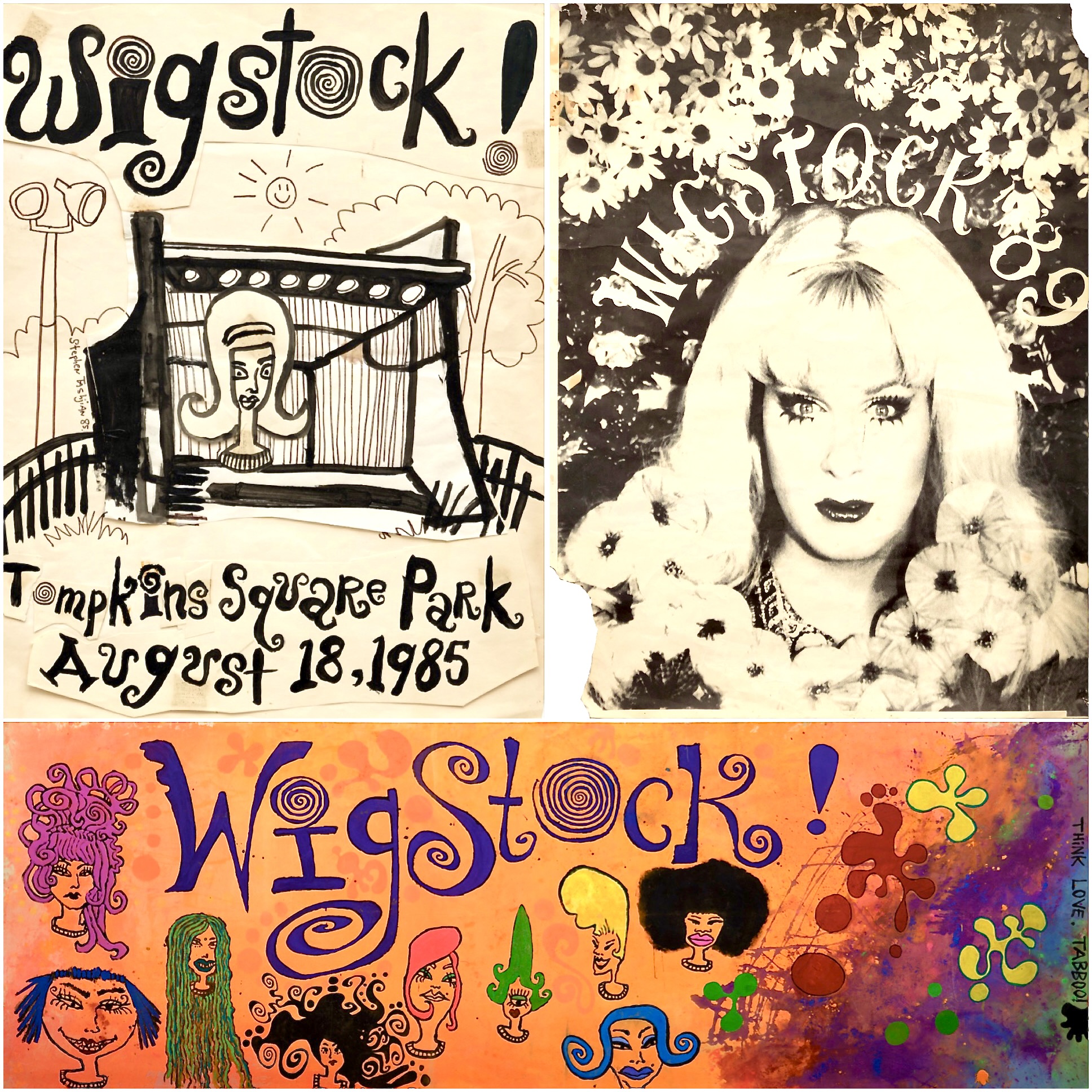

Illustrations by Tabboo

Forty years ago this summer, Wigstock made its grand, volumized entrance right here in Tompkins Square Park. New York City still misses it. Today, of course, the world of Wigstock is all around. Even the most dedicated gearheads know that “RuPaul’s Drag Race” isn’t a dirty, cacophonous motorsport. Its host—an early Wigstock performer of course—has led the TV show to 24 Emmys over 17 seasons, and has spawned half a dozen spinoffs as well as franchises in 17 countries worldwide. Similarly, FX’s series “Pose” won an Emmy for actor Billy Porter, a Peabody award for the show itself, and all-round praise for its three seasons that introduced millions to “voguing.” Drag brunches, drag bingo, drag book readings—they’re everywhere! And on June 27 this year, as part of Pride Month, New York’s annual Drag March will convene in Tompkins Square Park at 7:30 p.m., whereupon its irreverent band of cross-dressers will parade with all the spontaneous gusto of early Wigstocks to the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street to honor the legacy of all those who have fought over the years for LGBTQ+ rights.

But none of this popularity, this exposure and acceptance—current Washington administration excluded—would exist in NYC today were it not for Wigstock, and what happened in and around Tompkins Square Park in the wee small hours of September 3rd, 1984. This is where our story begins.

Sunday evenings at the Pyramid Club were drag heaven back then. The Avenue A club ran from 1979 to 2020, when it was shuttered by covid, then sporadically until 2022, when it closed for good. For all its longevity, its wildest times were in the early- and mid-1980s, soon after it switched from miserable bar to flamboyant performance space, right before AIDS claimed hundreds of lives in the city’s arts community, and a little longer before gentrification would change the nabe for good.

It was at the Pyramid in 1982, for example, that RuPaul made her drag debut, thus joining a drag hall of fame that could include Lady Bunny, Lypsinka, Tabboo, Flotilla DeBarge, John Kelly, Joey Arias, Linda Simpson, and many, many more. Still, while Pyramid patrons also included Keith Haring, Andy Warhol, John Sex, and Quentin Crisp, it was not only a gay bar. Madonna, Iggy Pop, and Debbie Harry were regulars. Hetero hardcore punk bands like Flipper played. The multi-talented Kelly describes the overall neighborhood vibe as “Artists, outsiders, affordable rents. Gay, straight, punk, rock and roll—the last gasp of physical bohemia.” Anyone with an itch for artistic freedom was welcome.

The Sunday show behind Wigstock began at the Pyramid mid-afternoon and rolled on until closing at 4 a.m., at which point Lady Bunny and a squad of well-oiled performers retired with their six-packs to the decrepit bandshell in Tompkins Square Park. There they put on a ramshackle show—not for the first time—until sometime after dawn, when they headed to a nearby diner for breakfast. Over some strong, medicinal coffee, the conversation turned to putting on a proper show in the Park—out in the open, during the day, for the public, in the bandshell, the bill to be filled with performers from the Pyramid. Lady Bunny suggested, somewhat optimistically, that it would be just like Woodstock in ’69.

No one knows for sure who at that moment exclaimed “Wigstock!!!”, but everyone agrees that it was Lady Bunny who took the idea and ran with it—all the way to City Hall, where she secured a permit (rumor has it that a $50 backhander was involved), and started making plans for the world’s first Wigstock: Sunday, August 18, 1985.

The inaugural edition was delightfully inspired and messy. The Pyramid put up $1,000 to cover the cost of sound system rental and other props; Pyramid regular Tabboo—now an internationally acclaimed artist—designed promotional posters, fliers, and the original set décor that read “Wigstock: Love, Peace, Wigs.” Everyone pitched in.

Fittingly, Lady Bunny was Wigstock’s first performer. After shimmying around to intro music in a long, disheveled blonde wig and a frilly black pants/dress combo, she opened with Carole King’s lyric, “I feel the earth move…under my feet”—the only line from the song that she knew—and just like that the Wigstock movement was alive.

If the de facto Pyramid house band The Fleshtones (playing as “The Love Delegation”), provided some semblance of a recognizable musical concert, then the rest of the line-up kept the afternoon comfortably off-kilter. One of drag performer Lypsinka’s numbers, for example, had her miming to “Downtown”—but not the Petula Clark version that two decades earlier had topped the charts in every country on earth that had a jukebox or a radio station. The Tompkins audience would instead hear, via Lypsinka, the Billboard-charting version of “Downtown” by “Mrs. Miller,” an oddball, 59-year-old from Joplin, Missouri, who reconstructed Pet’s megahit by both singing and whistling. Can you mime a whistle? Lypsinka did—and the crowd went nuts.

It was that kind of show: A surprise and a laugh in every bite. Lady Bunny put it best: “The theory is that we put on Wigstock every year just because there are so many housewives and children who cannot make it to the nightclubs.”

The last song of the first Wigstock became the festival’s anthem. John Kelly already was a master at inventing personas and devising performances for them, and his “Dagmar Onassis” character—“the fictitious daughter of Maria Callas and Aristotle Onassis”—had been entertaining the Pyramid all summer. Now Kelly decided that Dagmar had to play Wigstock, and that Dagmar would sing Joni Mitchell’s “Woodstock.” (Mitchell did not play Woodstock, but the song is on her “Ladies of the Canyon” record as well as on the B-side to her “Big Yellow Taxi” single.)

“The moment they said they were doing the festival,” Kelly recalls, “I told Lady Bunny I had to be in it. And sure, I’ll wear a wig and a dress. So I did Joni Mitchell, with the high voice. That was like vocal drag. You’re f****** with people’s expectations when a man sings in a high voice.

“For the first Wigstock I had [Pyramid performer and manager, now deceased] Brian Butterick on piano, and Jesse Hultberg on guitar, and we all dressed like Joni Mitchell. The next year I had Brian dress like George O’Keefe, because Joni knew George O’Keefe, and Jesse was Neil Young.

“I changed some of the lyrics. At the very end of the song, instead of singing ‘And I dreamed I saw the bomber jet planes’ I changed it to ‘I dreamt I saw the drag queens…spraying hairspray in the sky. And they made all the yuppies die…Across our nation.’

“Also at this time, AIDS was coming in—I lost my first partner in 1982—so the next year I changed the ending lyrics to ‘I dreamed I saw the drag queens…and they were all dressed up like maids. And they had found the cure for AIDS…across our nation.’

“It was amazing. By the time I sang, it was almost dark, and everybody lit and raised cigarette lighters, with bodies swaying, holding one another in solidarity and recognition. It became the anthem for Wigstock—and the beginning of my singing career. I had never sung live before.”

Kelly is telling us this not in Tompkins Square Park but outside a coffee shop on an overcast morning in Provincetown, Massachusetts. The previous evening he had performed a selection of Mitchell songs at an event organized by local arts organization Twenty Summers. The double bill paired him with Rutgers English professor Paul Lisicky, who read from his new book on Mitchell, “Song So Wild and Blue.”

Kelly had no need for costume here in the barn where painter Charles Hawthorne had convened the first Cape School of Art some 120 years earlier. Jeans and a light black sweater. No blonde Joni wig over his thinning hair. “This isn’t like the first Wigstock,” he told the audience. “I feel a little out of character.” There was little reaction from the floor, which was predominantly LGBTQ+, artistically inclined, not terribly young, and mainly New Englanders. Tompkins was a bit too distant.

It has become distant to Kelly, too. “Wigstock was a great idea,” he says now. “There wasn’t a lot of that performance around at the time, so the idea of putting something out in the open, literally, in a big kind of fest—not a massive festival, but bigger than just a night—was great.

“Even the locals appreciated it, meaning the people that were maybe living further east [than Tompkins] or had lived there a while. The area still was dangerous—which was great, too, because that kept out the assholes and the wimps. But then Wigstock got more popular, and got bigger, and then the riots happened in 1988, and after that, things just changed. Wigstock became a bit of a nightmare. We were forced to do it one year in Union Square!”

That was in 1991. Following the ’88 riots, the City had shut down Tompkins to rearrange and renovate. Although the bandshell was a victim of the redesign, Wigstock returned to Tompkins in 1992 and ’93. But in 1994, the Giuliani administration moved it all the way over to the wide-open Pier 54 on the Hudson at W14th Street. It was convenient to the gay scene of the West Village, but it lost the compact feel of a small city park. “Not having it a green space was less fun,” Lypsinka told the EVCC. “The pier seemed too big, and there was no place to hide from the sun, but it didn’t stop the crowds from coming.”

They came until 2001, when Wigstock returned to Tompkins as a subsidiary of the Howl Festival. Wigstock was back…but was losing its mojo. After a couple of rainouts Lady Bunny, still in charge, called it quits.

Until, that is, 2018, when she joined actor Neil Patrick Harris to revive Wigstock on the roof of Pier 17 at the South Street Seaport. The actor, who four years earlier had played “Hedwig” on Broadway, co-produced a movie of the concert and all that led up to it, the result screening at the Tribeca Film Festival and winning a slot on HBO’s 2019 program line-up.

This “Wig” movie covered more than just the gig. It dug into the rise of drag from underground to rooftop and highlighted how many of the Pier 17 acts had long performed at “Bushwig,” the Wigstock progeny born in Brooklyn in 2012 as the drag scene, like many of the arts, was emigrating over the East River to escape the cost of gentrification.

This ”Wig” concert was far from the Wigstock of Tompkins. It was big and glittery and reeked of production values but did not crackle with community fun. No one paid $300 to rent a sound system. No one mimed Kabuki as drag queen Olympia did in full Japanese dress in ’87 or sang a painfully brilliant falsetto version of “Born Free”—accompanied by clarinet and cymbals—the way The Ladies Auxiliary of Avenue A did in Tompkins in ’86. Lypsinka did appear on Pier 17, but her standout turn remains her miming to Lauren Bacall in Tompkins in ’93. For that cover of “But Alive”—from the musical “Applause”—Lypsinka had four back-up dancers and a co-star in 3-feet-1-inch-tall David Steinberg, an actor marginally better known for appearing in the Ron Howard movie “Willow.” The Tompkins Wigstocks really were in a league of their own.

But decide for yourselves. Watch the three Wigstock movies below and be sure to check out “5NinthAvenueProject” YouTube channel for videos by Nelson Sullivan, who chronicled much of Wigstock before dying of a heart attack in 1989. The movies:

- “Wigstock—The Movie.” The 1987 original by Tom Rubnitz. The opening song, “The Ballad of You & Me & Wigstock,” sung by John Sex and Wendy Wild, goes “Tompkins Square Park on Avenue A…that’s where I’ll wear my wig today”—and the next 20 minutes could be the best home movie ever made, complete with half the neighborhood coming out to party with all their mad cousins and a cavalcade of daft aunts. The editing is rough, the camerawork shaky, but it captures the inseparable spirit of the performers and the audience perfectly.

- “Wigstock—The Movie.” Same title, different film. A proper music documentary by Barry Shils. Goes behind the scenes and into the audience as well as on stage in both 1993 and ’94. Highlights include Mistress Formika singing the Age of Aquarius, Lady Bunny telephoning City Hall to ask if she could put a wig on the Statue of Liberty, and one of the first show-stopping appearances by RuPaul.

- “Wig.” The big time. The rarefied air of an HBO Original! Shot on top of Pier 17 at the South Street Seaport in 2018. Covers the rise of drag via Wigstock but also spends a lot of time in Brooklyn with the cast of the long-running offshoot “Bushwig.” Neil Patrick Harris brings star power and attracts production $$$, but for all its splendor, it lacks the East Village charm that make the first Wigstocks so communally euphoric. Near the end, while miming to Cher’s “Just Like Jesse James,” Bushwig trans queen Charlene Incarnate whips off her knickers and, as the British would say, shows off the crown jewels. The state of the game perhaps, but it wouldn’t have happened in Tompkins. (Stream it in Max)